Chart of the Week: Moving from the Juvenile to Adult Justice System

Today's Chart of the Week comes from the paper “Estimating the Impact of the Age of Criminal Majority: Decomposing Multiple Treatments in a Regression Discontinuity Framework” by Michael Mueller-Smith, Benjamin Pyle, and Caroline Walker. The paper looks at the effect of moving from the juvenile justice system to the adult justice system by examining cases in Detroit. When looking only at the effect of moving from the juvenile justice system to the adult justice system, two countervailing effects are apparent. Those in the adult system are less likely to commit crimes or be convicted of crimes in the future, but they also have lower earnings and employment. Therefore, being tried in the adult system improves recidivism risk, but it has a negative effect on future labor market outcomes.

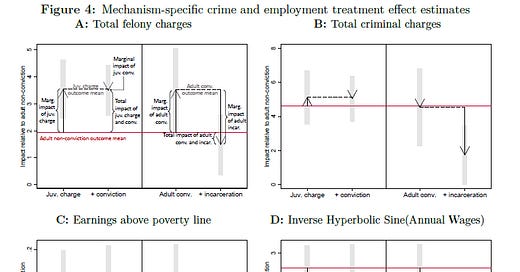

The authors explain this mixed effect by stating that the move from the juvenile justice system to the adult justice system has multiple different treatments. For example, juveniles are less likely to be convicted at all, and their convictions are less likely to stay on their permanent record, which has positive labor market effects. However, they are also less likely to be incarcerated, and incarceration, at least during the period of incarceration, reduces recidivism, which has a negative effect on recidivism. To go beyond just explaining this, the authors disaggregate the effect into these two different mechanisms by predicting, for each individual on either side of the age of majority threshold, what their sentence would be. Using those predicted sentences, they can disentangle the effect of the two mechanisms: the conviction mechanism versus the imprisonment mechanism. Their Figure 4 shows this disaggregation, so you can see, for each of these sets of people, the effect of the conviction on the outcome versus the incarceration or supervision period.

In the first panel, you can see the effect on total felony charges. On the juvenile side, the marginal effect of having a charge versus having the case dismissed actually increases the likelihood of having a future felony charge for both juveniles and adults. The low supervision rate for juveniles means that the effect of having a juvenile conviction doesn't increase or have a significant effect on the likelihood of a future felony charge. In contrast, because adult convictions typically come with a period of supervision, you can see that the adult conviction actually results in a significant decrease in future felony charges, which ends up being a small decrease in the overall probability of having a future felony conviction from being in the adult system versus the juvenile system. In panel B, you can see that this effect is even larger for those adult incarcerations when looking at total criminal charges.

However, when looking at earnings in panels C and D, you can see that incarceration has a negative effect on future earnings, especially when looking at annual wages versus just having earnings above the poverty line. There is a significant effect of having a conviction, and then a further effect of having an incarceration in the adult system.

Beyond the results of this method for this paper itself, as the paper discusses, this method could be useful in other settings. There are many situations where an event occurs, and you can measure the total effect of the event, but that event involves several different mechanisms. For instance, in a completely different context, this method could be useful in understanding the motherhood penalty. Understanding the motherhood penalty requires understanding the long-term effects of a higher likelihood of leaving the labor force, of taking a part time job, of changing employers to a more family-friendly firm, of remaining in the same firm but with lower earnings growth, etc. You could potentially use the same method if you had a way to predict those reactions to having a child and disentangle the effects of each.